A few editorial notes before I begin this tale of adventure. In 2003, I was still a budding photojournalist. I hadn’t quite figured out my artistic style nor was as technically skilled as I am now 14 years later. I was green and it shows. Also at the time I had just begun my journey into digital photography so this entire trip was shot on film. I have left the imperfections in the medium through the editing process. I feel like it gives grittiness to the images that you no longer get with the digital age. And so the tale begins…enjoy!

I love looking back on photographs from the travels I have taken throughout my years on this planet. They instantly bring into focus the memories and experiences I have had that may be whitewashed with the passing of time. That is the power of photography and of storytelling in general. Everyone has a story to tell that is unique and their own. These tales can bring a smile to your face or a tear to your eye. Regardless of the subject, the narratives of different people weave together the bright and beautiful tapestry of life.

I traveled to El Salvador back in 2003. Stepping off of the plane into the humidity and heat wasn’t so foreign having grown up in the southeast. Getting through customs was easy, and like most final security checks in the southern hemisphere of the Americas, I had a fifty-fifty chance of being screened further with a very old game of red light, green light. I push a button and wait with slightly baited breath for the electrical impulses to randomly select my color. After a brief eternity the light turns green and I am free to enter the bustling metropolis of San Salvador.

I am here to visit my friend Ryan. He has spent a few years in the country volunteering with the Peace Corp. I see him almost immediately bounding towards me with a head full of curly blonde hair and a smile on his face. He stands out not only for the hair but because he towers over the majority of the people on the street. We catch a ride on a bus to the place we’re staying over the next few days. A house used by fellow volunteers that mainly work in the city. The bus ride itself is an immediate indoctrination to the culture of the smallest country in Central America. There are older women, grandmotherly with their wrinkled and sun drenched faces, holding onto chickens. They sit next to their children and sometimes grandchildren. Three generations traveling together through the city heading to who-knows-where. There are people heading to work, younger kids listening to a radio with music blaring through the speakers, couples cuddled together. The bus is packed with people and their belongings as we jump and jostle through the streets, standing in the center aisle, taking in everything there is to see.

We settle in to a room at the house and the next few days turn into a blur. There are moments and events that stand out; a local soccer game in a small stadium, walking the maze of streets, people watching in large public areas. After an evening out we wind up in a small alley with the smell of something delicious wafting down the narrow corridor. It’s my first experience at a pupuseria. A woman stands next to a small cart with hot griddles. She stuffs thick, almost bread-like, tortillas with beans and cheese and meat and proceeds to grill them together. I add spicy cabbage slaw and even spicier hot sauce to top off this traditional delicacy. The taste buds in my mouth explode. I end that night full and happy.

Most of the next day is spent at the Metropolitan Cathedral in downtown San Salvador with thousands from the community all gathered to remember the life of Archbishop Óscar Romero y Galdámez, who was assassinated while offering Mass in 1980 for speaking out against poverty, social injustice and torture. The church pews are filled with people. So are the steps that flank the sanctuary. People sit, they pray, they light candles and they talk quietly within the reverence of the cathedral. The archbishop’s remains lay entombed in the crypt below. It is a place to remember the history that has shaped the country into what it is today. A man sitting beside us strikes up a conversation. With Ryan acting as a translator for the three of us, he asks why we are here. Ryan talks about his Peace Corp work and I about my love of travel and photography. We talk about the violence that led to the archbishop’s death and about the possible impending violence of the political elections that were to happen in the next few months. I asked him why he came to the cathedral this particular day and he said to remember all of the terrible events and violence that has shaped his home in the hopes that remembering how ugly it was will help to change the future. It’s a conversation that has stuck with me for the past 14 years.

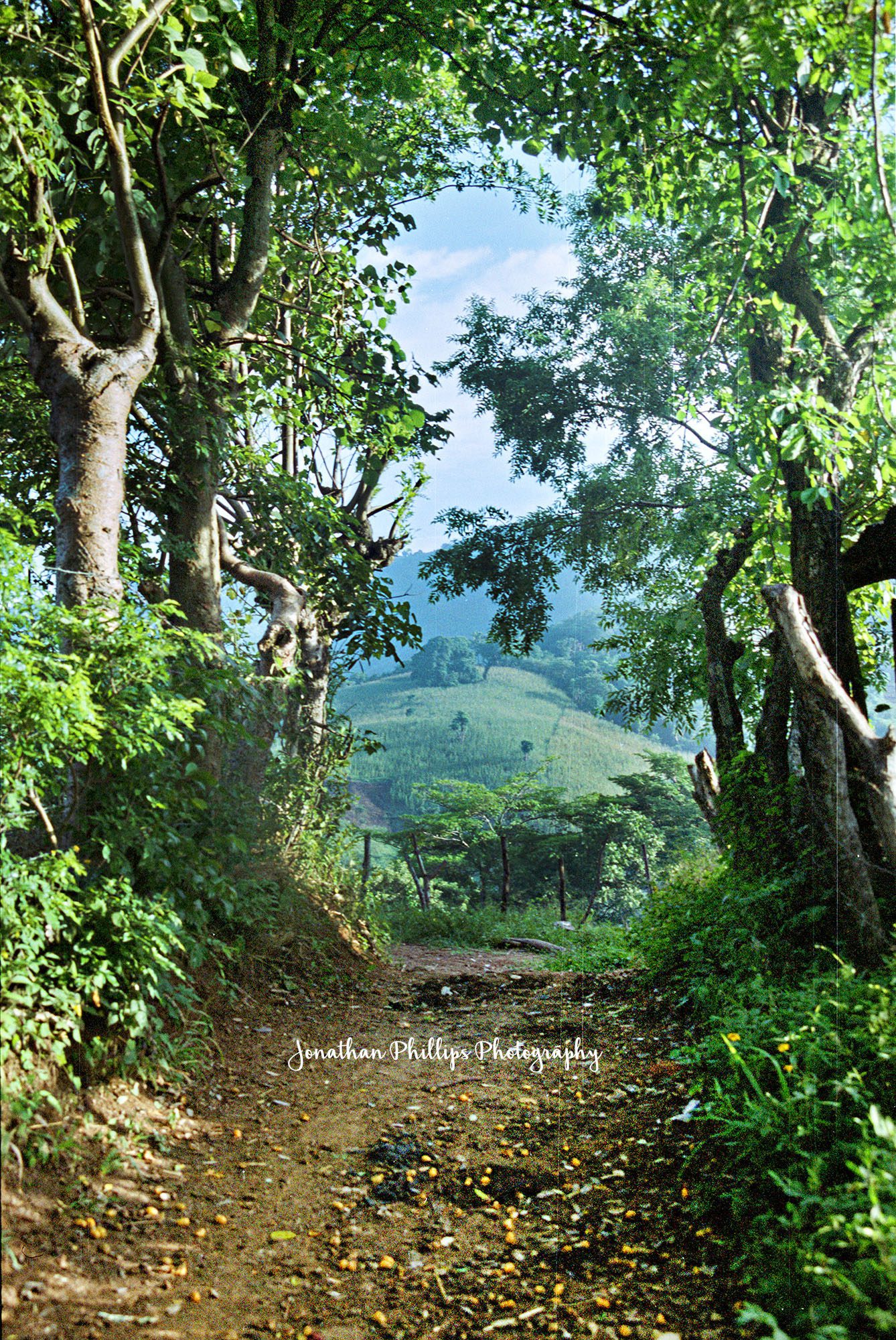

Tired of the busyness of the city, we head to the bus station early the next morning to catch a ride. We are heading out into the cantons, the smaller rural areas of the country, with the final stop being San Isidro Morazan, the mountain village that Ryan calls home. It’s going to be a long travel day. The ride from San Salvador to San Isidro can be anywhere from six to 14 hours long depending on a few things like weather, the driver, the traffic, and the actual road and whether or not it is covered in a rock slide or mud slide or some other catastrophe. The road through the rainforest and up into the mountains is mostly dirt. It is bumpy and long. Although sometimes frightening, our driver deftly swings the old school bus around hairpin curves at high speeds. With a few stops along the way we make it to the small village in about eight hours.

San Isidro Morazan embodies the quintessential village that dots the rainforests and mountains in the rural areas of El Salvador. It sits above the Rio Torola River that snakes through the valley floor below. There is a church, a one classroom school, a dual purpose soccer and basketball court, houses made from a combination of cinder blocks, brick and mud, a small market to buy essentials for meals like eggs, vegetables, beans and tortillas usually made and grown by neighbors. The streets are cobblestone and mud. Young children play in the streets as farmers and ranchers sit together to trade stories, talk about the weather, which can be a 30 minute conversation at times, or get their day started with a cup of coffee or a smoke.

Ryan’s house is made of cinder blocks on a concrete slab with a roof made from sheets of corrugated tin. Inside a hammock hangs from two of the walls. There are two small tables, a propane camping stove, a washing tub, a couple of shelves hold books, a small radio and an alarm clock. A map of the world is tacked to the wall near an old mural depicting a few trees, a mountain, a lake and a butterfly.

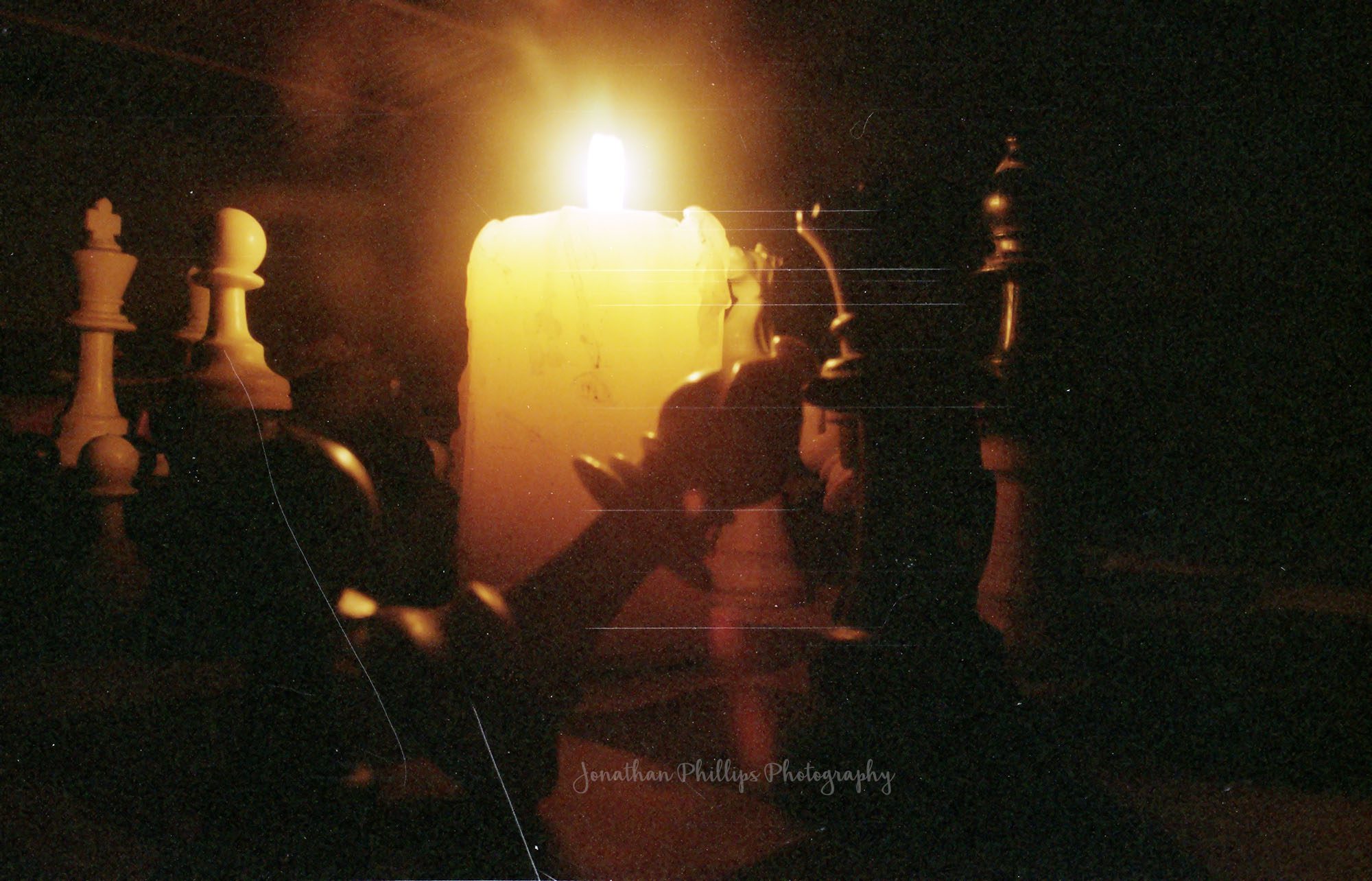

The next few days are spent playing the guitar, walking the streets, talking to the farmers and neighbors that call the village their home. My Spanish is pushed to its limits. At night, power is spotty so we play chess by candlelight. One particularly late evening I hear dogs barking off in the distance. Soon the sound gets closer as if in some scene from Lady and the Tramp the canines are communicating throughout the area. The barking moves up the valley, through San Isidro itself and then onwards towards the next mountain and as the sounds fade Ryan and I look at each other to make sure the experience really happened. It is surreal.

The next day we hiked a few hours down to the banks of the Rio Torola. The water is swift and refreshing from the heat of the day. The trail back up to the village is somewhat grueling as the steady, steep incline works my muscles to the point of exhaustion. I slept like a baby that night.

While in the Peace Corp, one of the programs that Ryan tried to implement for the region was bee keeping. The concept had been newly introduced when I was in country thanks, at least in part, to my friend. The idea was beginning to take hold as a viable way to earn a living, or earn extra income, for farmers that had historically been slashing and burning their fields after harvest season for generations. The soil had been taking a beating and was starting to show the effects with smaller crop yields so this was a way to try and convince the population that you can let the terrain heal itself while still earning the much needed income. Ryan had been growing and expanding hives for a year and a half and they had been producing some amazing honey. We were to meet with a group of farmers interested in learning the process and Ryan was excited as word of mouth is important in the Salvadoran culture and it was still a challenge garnering interest for the program. We hitchhiked out of San Isidro on the back of a flatbed truck, down the mountain and a few towns over to where his hives were located. The farmers, Ryan and I donned the protective gear to keep from being stung in the face. The buzzing sounds steadily increased as we hiked a little ways into the surrounding rainforest and arrived at the site. More than a half dozen active and productive hives greeted us. The hives were smoked to calm the bees so they could be opened and inspected, showing the simplistic layout of the structure and the honey the insects can produce. The interest in his project grew leaps and bounds that day.

Time was getting short. I only had a couple of more days left in this beautiful country. One of the downfalls of traveling for me is having to leave whatever exotic locale I visit. To return to a sense of normalcy leaves me with a terrible longing to be back out in the world, to keep exploring, to keep looking for the next adventure which I am sure is just around the corner. What better way to combat this impending feeling than to hike an active volcano.

Volcán de San Miguel, also known as El Chaparrastique, rises almost 7,000 feet into the air. Although the volcano most recently erupted in 2013, at the time I visited a decade earlier, all was quiet. The hike took me above the trees and to a hot spring surrounded by ash laden mud inside of the caldera. Locals believe that the mud and the springs that dot the volcano have healing properties. I cannot say for sure but my nerves definitely eased as my feet sank into the silty grey muck.

That feeling stayed with me through my final day and as I boarded my plane to return home I reflected on my experiences. The differences between two cultures, once seemingly so distinct from one another, are actually closer than on first inspection. We all strive to make our lives better. We all crave some sort of connection with others. Maybe we should try to bridge the gap between what we think we know and what our experiences show us as we travel.